High school students should not need ‘phone police’

January 14, 2016

Furiously scribbling notes in math class, a student hears a muffled noise from within his backpack: the buzz of his cell phone. Hoping to make sure his parents are not contacting him with an urgent matter, he reaches into his backpack for a mere second. However, before he can send a quick response, he hears his teacher’s booming voice command him to hand the device over. The next day, he receives a note for a thirty-minute detention after school–an exaggerated punishment for sending a harmless text message in class.

According to the Homestead Student Handbook policy, “If you are in violation of the policy concerning electronic devices… the device will be confiscated and kept in the office until the end of the school day.” Although many students do use their phones in class for unnecessary reasons, this should not be teachers’ assumption. Often times, students receive texts from their parents or their bosses about after-school plans, and these individuals sometimes expect an immediate response. As a maturing adult, I would appreciate the benefit of the doubt. However, according to the handbook, I do not even possess the right to explain the nature of my phone use, as it states, “When asked to surrender the device by a staff member, students should do so immediately or they will be considered insubordinate.” Attempting to defend myself in this situation results in accusations of noncompliance to school policy. Furthermore, many teachers refuse to listen to such explanations anyway. They simply expect that phones automatically indicate frivolity.

“What many adults do not understand is that the majority of the time teenagers are on their phone is not for insignificant purposes,” Katie Writz, senior, said. “My cell phone serves as my calendar, navigation system, camera (used for taking pictures of assignments or notes), calculator, notepad and just a way to communicate with whomever I may need to send a message to at that particular moment.”

According to Linda Matchan of the Boston Globe, “It is the most vexing issue of the digital age for teachers and administrators: What to do about students’ cell phones? Some maintain that smartphones and other devices in schools are crucial to being competitive in a global market, while others insist that phones and tablets distract students, compromising their learning and focus.”

I understand that many younger students may need help directing and redirecting their focus. By the time students enter high school, however, they should begin to learn how to control their own attentiveness. Juniors and seniors, who have been doing the whole “school thing” for over a decade, should especially understand what hinders their ability to learn and what does not. Chances are, for most students, quickly looking at a text message won’t do too much damage. That being said, other students might have more trouble, and of course, rules must be enforced universally. Yet, even for students who become engrossed by their iPhones during class, there comes a point where this becomes their own responsibility, not their teachers’. If college-bound students decide to spend 73 minutes on social media rather than focusing on the lesson, then that is their problem, and they should face the consequences of a bad grade themselves.

“By the time a student has reached a high school age, I believe they should now have obtained the maturity needed to make their own responsibilities, especially with college in the near future,” Writz said.

Homestead’s mission statement is to “equip all students with transferrable skills… [and] promote academic independence.” Policing students’ phone use does not fit into this mission. Students, specifically upperclassmen, should learn what helps and what hurts their education, and they, alone, should take responsibility for the distractions they bring into their lives.

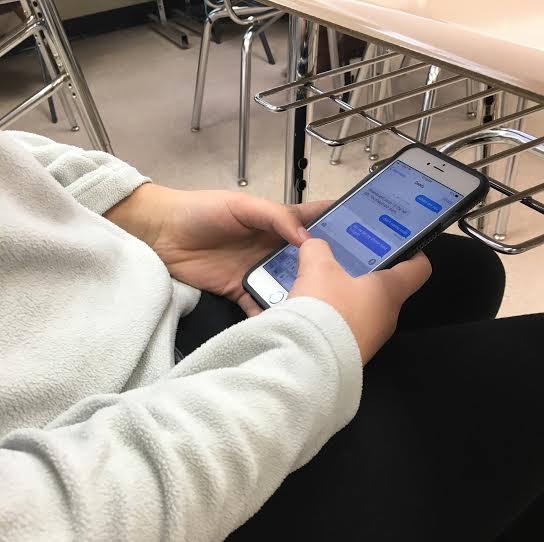

I am not arguing that students should spend their class period scrolling through their Instagram feed. At this point, the issue is no longer one of distraction, but of disrespect towards the teacher. Most of the students who slyly text underneath their desks or from within their backpacks, however, don’t do so because they mean to be disrespectful. The reality is, most teenagers are obsessed with–even addicted to–their phones, and it is difficult to keep their attention away from social media and text messages for the duration of a 73-minute class period. In a study conducted by the Pew Internet and American Life Project and the University of Michigan, researchers found that “in schools that permitted students to have cell phones, 71 percent of students sent or received text messages on their cell phones in class. In the majority of schools –those that allow students to have phones in school but not use them in the classroom – the percentage was almost as high: 65 percent. Even in schools that ban cell phones entirely, the percentage was still a shocking 58 percent.” Obviously, even a complete ban on cellphones in school cannot eradicate in-class messaging.

This data does not demonstrate disrespect for school rules, but rather a greater problem among today’s teenage generation. Looking around the cafeteria or in the hallways, this problem becomes obvious as students, sitting around tables with their peers or walking through the halls side-by-side, are engrossed in their phones rather than in real conversation. As a teenager, I can attest to the feeling of nakedness when my phone is not near or in my hand, and unfortunately, a 30-minute detention will not cure this addiction. Rather than snatching our phones away and placing us in time-out, teachers should discuss the greater problem plaguing us and society as a whole.

“I think that phone addiction is a serious reality,” Mrs. Angelina Cicero, English teacher, said. “I have even myself struggled with it. There is something about the constant communication that is enticing.”

Phone addiction will not end just because someone says, “Stop using your phone.” The real goal should be creating a culture where, as Mrs. Cicero said, students “philosophically agree” with the fact that phones, when used for non-educational or non-urgent purposes, do not belong in the classroom. This begins with students and teachers forming a relationship built on trust, respect and integrity. When students feel that their teachers view them as mature young adults, their affinity to display respect for the teacher and for the learning environment increases.

“It’s more about building relationships,” Mrs. Cicero said. “Instead of it being, ‘I’m going to comply with the rule, it’s about getting people to a place where they philosophically agree with the rule. The more you can have a front-end conversation about the reasons for something, the more you can create a culture where it’s not just compliance.”

Anonymous • Jan 15, 2016 at 7:31 pm

I agree that students deserve the right to defend themselves for use of technology. However, parents and bosses contacting students during school hours (through text) should be fully aware that these kids are in school! If there is a family emergency, parents should contact the school for the student to be excused. Less than a decade ago, if a student needed to talk to his mom, he had to go to the office and use the landline. Just because there is technology that makes communication easier for kids and parents, does not mean that it should be an acceptable excuse. If a student is supposed to taking notes in class and he is instead texting his mom, how is he going to do well in math? Also, math requires a graphing calculator at some point so sorry, your cellphone’s calculator isn’t going to cut it. I’m tired of everyone assuming that every kid has the ability to text his mom whenever he needs something or take pictures of the assignment for the day. Some students do not have that privilege. Teachers are no longer “minding the gap” and saying, “Look it up your phone!” rather than using a dictionary. Yes, google may be faster but what if a student can’t just google it. This article comments on the extreme rule enforcement that takes place but I find it to be the opposite. Moving forward with technology is the best plan of action. But until all students are treated EQUALLY, there is no reason for phones to be used (excluding in-between periods and lunch).