Politics Playbook: Explaining contested conventions in the GOP

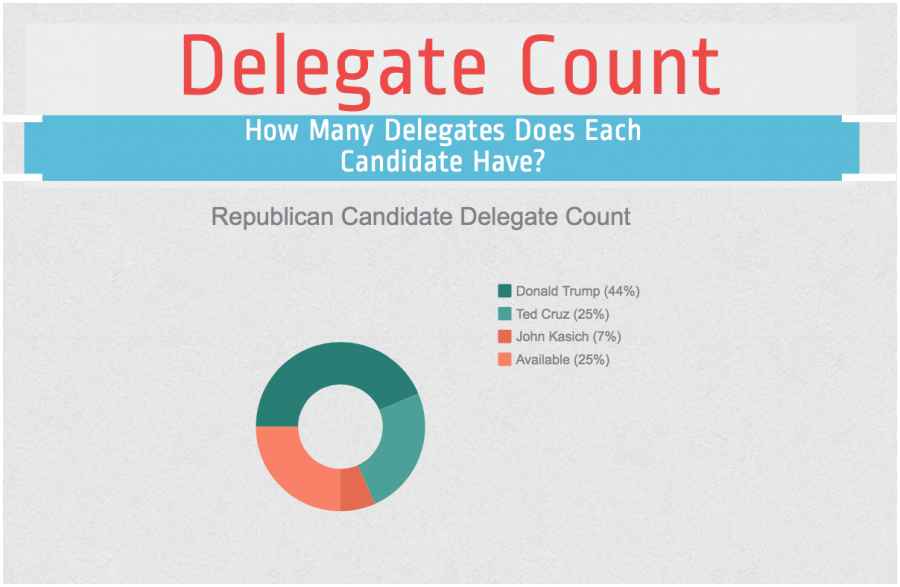

According to current delegate counts, Mr. Donald Trump, Republican presidential frontrunner, holds 996 pledged delegates; Sen. Ted Cruz, Republican presidential candidate, holds 565; and Gov. John Kasich, Republican presidential candidate, holds 153. In order to win the nomination, one candidate has to receive the necessary majority of delegates, which is 1,237.

Deciding party nominees, diverging from state primary results and revising outcomes, contested conventions serve as a contentious fixture of the political party system. Although generally obscure, this staple of election season rocketed to the forefront of national attention after various presidential candidates have invested their hopes of winning the nomination in a potential contested convention.

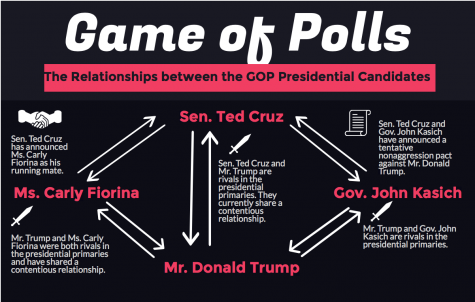

According to CBS, “Neither Ted Cruz nor John Kasich can win the Republican presidential nomination in the remaining primaries. Both are counting on the first contested convention in 40 years.”

Showcasing how two of the Republican candidates are dependent on a contested convention, the Associated Press has declared that it is “mathematically impossible” for Sen. Ted Cruz, the second-place Republican frontrunner, to win the nomination in a first ballot.

Sen. Cruz acknowledges his need for a contested convention.

“We are headed to a contested convention. At this point, nobody is getting 1,237,” Sen. Cruz stated. “Donald is going to talk all the time about other folks not getting to 1,237, but he’s not getting there, either.”

Also, to attempt to win the nomination despite lagging behind in delegate pledges, Gov. John Kasich continues to aggressively campaign in the primaries, hoping to siphon away enough delegates that a contested convention would be announced, a situation in which he could win the nomination.

In response to his opponents’ strategies, Mr. Donald Trump, Republican frontrunner, derided its potential use in the case that there is no clear frontrunner at the Republican National Convention.

Mr. Trump explains his disapproval of contested conventions and the rules they follow.

“I think we’ll win before getting to the convention, but I can tell you, if we didn’t… you’d have riots,” Mr. Trump stated. “I’m representing… many, many millions of people.”

Elaborating further, Mr. Trump said, “If you disenfranchise those people and you say, ‘well, I’m sorry, but you’re 100 votes short,’ even though the next one is 500 votes short, I think you would have problems like you’ve never seen before. I think bad things would happen, I really do.”

Fueled by Mr. Trump’s remarks, the country exploded in heated debates over this issue, with one side deriding contested conventions as a symbol of political elitism and the other attempting to justify their existence within the presidential race.

However, despite the large amount of controversy surrounding contested conventions, not many Americans are able to state what they entail. So one question remains: what exactly are contested conventions?

During most presidential election seasons, what typically occurs is that, in each party, the candidate who has won the majority of his or her party’s delegates–1,237 out of 2,285 for Republicans and 2,383 out of 4,765 for Democrats–wins the nomination and is then officially endorsed by the party for the presidency.

However, according to Mr. Josh Voorhees, senior writer for Slate, in the case that no candidate has won the necessary majority of his or her party’s delegates, then a contested convention occurs.

Mr. Andrew Prokop, political analyst, provided an explanation as to what exactly happens in a contested convention.

As of right now, in the first ballot, “around 95 percent of GOP delegates are bound to particular candidates,” meaning that 95 percent of candidates, based on the results of primaries or caucuses in their respective states, have already promised to support Mr. Trump, Sen. Cruz or Gov. Kasich, Republican presidential candidates. During the National Convention’s first ballot, the remaining candidates will conduct “furious efforts to woo the [5 percent of delegates] who are unbound” as well as the delegates who may be “released” by the former candidates, and if the results lead to no one candidate receiving the necessary majority of delegates, then a contested convention would occur and a second ballot would be initiated.

In the event of a second ballot, the GOP would release a majority of delegates from their pledges.

While different states have established different rules for when the “bound” delegates may become “unbound,” most states stipulate that they may be released from their pledges “after a first round of inconclusive voting.” Thus, in a second ballot situation, the GOP will release a majority of delegates from their pledges and leave only “25 percent or so” bound, permitting the remaining 75 percent to support whoever they wish, regardless of state primary results.

Then, if no candidate wins the majority during the second ballot, the GOP will organize a third ballot, causing “even more delegates [to] be released from their pledges.” This procedure would repeat itself for “as many rounds of balloting as it takes for one candidate to get a majority.”

Ultimately, what this means is that if a contested convention should occur, a candidate other than the Republican frontrunner may win the GOP’s nomination for president due to the system’s rules.

To further strengthen this possibility, because a political party is a private organization rather than a governmental one, the delegates may “vote to change the rules [of the convention] however they’d like, even if those changes would hugely affect the outcome.”

Mr. Prokop elaborated further. “For instance, even if a majority or plurality of delegates are bound to vote for Mr. Trump, they’re not bound to vote in any particular way on rules,” Mr. Prokop stated. “So they could simply vote to change the rules to ‘unbind’ themselves, and then vote however they want.”

If this should occur, then delegates would be able to completely forgo the results of their state primaries and simply vote for whoever they wish.

However, while this possibility exists, it is “very unlikely” that the GOP would ever take “such an extreme measure” because it would “provoke too much outrage.”

In recent history, the “modern presidential conventions we’re used to are essentially rubber stamps” with the delegates voting according to the results of their states’ primaries or caucuses. As a result, if the GOP, in a move that would break modern precedent, ever heavily modified the rules to allow a candidate other than the frontrunner to receive the nomination, then there might be a “massive outcry” from constituents, a situation that the GOP “cannot afford.”

In addition, it would be “nearly impossible” for such an event to happen because “coordination amongst 2,472 delegates would be difficult” and because “some delegates will have loyalties to the political establishment in their respective states, but others may feel loyal to evangelical activists, the Tea Party movement, Mr. Donald Trump, Sen. Ted Cruz or even their state’s voters.”

Madina Jenks is a senior and a new copy editor for Highlander Publications. As a copy editor, her jobs are pretty simple: write and help others write....