Politics Playbook: Explaining the Iran nuclear deal

U.S. Secretary John Kerry testifies about the Iran nuclear deal before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on July 23, 2015 in Washington, D.C. The first significant talks in regards to the creation of the deal began in April 27, 2015, when Secretary Kerry and Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif met in New York during the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference, starting the technical drafting work on the annexes of the agreement. Image from Flickr

Inciting debates in Congress, representing the role of the Israeli lobbying force and establishing a key policy issue for the presidential election, the Iran nuclear deal has played a controversial role in American politics since its very conception in July. The deep rifts in opinions surrounding the deal expose the partisan splits among elected officials.

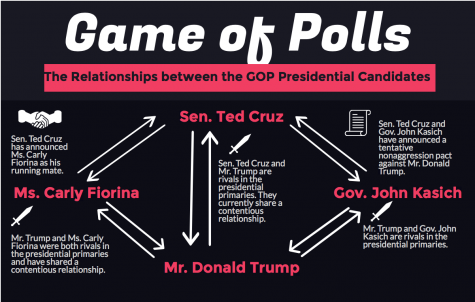

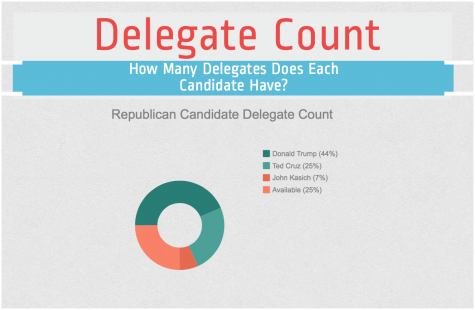

Republicans are unanimous in their repudiation of the deal, citing criticisms such as allegedly lax review procedures, lack of punishment for supporting terrorist organizations including Hamas and Hezbollah and alleged threats to Israel. Representing the widespread opposition towards this deal from Republicans, presidential candidates Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, former H-P CEO Carly Fiorina and former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee pledged a hardline stance on the policy, stating that they would “rip up the Iran nuclear deal on day one” if elected president, and that then they would “immediately reimpose sanctions on the regime and work to persuade allies to do the same. Even while taking a seemingly more moderate stance on the deal during the second Republican presidential debate, Ohio Gov. John Kasich stated, “The Senate should invoke the ‘nuclear option,’ [a procedure that would require 51 votes rather than 60], to stop the Iran nuclear deal.

Democrats, while accepting the bill, are lukewarm in their acceptance, viewing it as a bill that’s imperfect but the best option currently available. They indicate the suspension of Iran’s nuclear activities and the reaffirming of America’s position as a world power as the victories of the bill. Conflicted by their dueling loyalties to both the party and to their constituents, most Democrats ultimately, and reluctantly, voted in favor of the bill, with only four Democrats voting against it.

Senator Chuck Schumer, capitulating to the interests of his constituents, a large portion of which is populated by orthodox Jews, was one of only four Democrats to vote against the bill. Despite his official opposition to the bill, he urged a balanced view on the issue, saying “fair-minded Americans should acknowledge the president’s strong achievements in combating and containing Iran.”

However, despite the large amount of controversy surrounding the bill, not many Americans are able to state what the Iran nuclear deal entails. So one question remains: what exactly is the Iran nuclear deal?

Ever since November 1967, when Iran’s first nuclear reactor went critical, the question of Iran and nuclear weapons has posed a puzzling problem. In recent years, though, feeling threatened by the growing nuclear program of Iran, one of their greatest enemies, Israel employed a militaristic approach towards Iran and appealed to America for assistance. Balancing the demands to appease Israel, one of America’s key allies in the Middle East as well as a vital issue with the influential Jewish-American voting bloc, as well as the growing anti-war sentiment of the American people, America struggled to find an agreement that satisfied everybody.

The first talks that would culminate to the conception of the Iran nuclear deal began in April 27, 2015, when U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif met in New York during the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference, starting the technical drafting work on the annexes of the agreement. Debated amongst Iran and the P5+1 nations, a group of six world powers that joined together in 2006 in diplomatic efforts with Iran in regards to its nuclear program, including America, China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and Germany, a comprehensive deal was announced on July 14, 2015. On the same day, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) launched investigations into Iran’s nuclear military capabilities under the bill.

In July 19, 2015, in compliance with the 60-day review period mandated by the Iran Nuclear Deal Review Act, the Obama administration sent the comprehensive deal and its supporting documents to Congress to either be accepted or rejected. The next day, the UN Security Council unanimously passed a resolution endorsing the nuclear deal and the lifting of UN Security Council nuclear sanctions once the deal went into effect. Displaying Iran’s current willingness to adhere themselves to the stipulations set forth in the deal, in Aug. 15, 2015, the IAEA confirmed that Iran submitted documents to answer the last of the agency’s concerns about past activities that could have been related to the development of nuclear weapons.

The deal itself revolves around three main issues: ending Iran’s nuclear weapon program, lifting sanctions and ensuring compliance.

In regards to Iran’s nuclear weapon capabilities, the deal stipulates that Iran is prohibited from researching and developing advanced centrifuges, machines that produce enriched uranium fuel five or six times faster than the Pakistani-designed models that they currently rely on, for the next ten years.

More importantly, though, the Iran nuclear deal completely forbids Iran from producing plutonium, the key ingredient for nuclear bombs. Explaining how these restrictions on the creation of plutonium largely constrict Iran’s ability to produce nuclear weaponry, Mr. William J. Broad, science columnist for the New York Times, said, “As a fuel for weapons, plutonium packs a far greater punch than uranium, and in bulk can be easier and cheaper to produce.” Elaborating further, Mr. Broad added, “Of the 15,000 or so nuclear warheads on the planet, more than 95 percent rely on plutonium to ignite their firestorms.”

To showcase their support for the bars the Iran nuclear deal places on Iran’s ability to manufacture nuclear weapons, 24 leading scientists, including Richard L. Garwin, principal designer for the Manhattan Project and Washington expert on nuclear weapons and arms control; Pierce S. Corden, former director of the International Security Negotiations; and Howard Georgi, Harvard University professor, sent a letter to President Obama praising the deal. Referencing particular aspects of the deal, they said, “The agreement bans reconversion and reprocessing of nuclear fuel, and it requires Iran to redesign its Arak research reactor to produce far less plutonium than the original design and specifies that spent fuel must be shipped out must be shipped out of the country without the plutonium being separated and before any significant quantity can be accumulated.”

Taking a step further, they contradict the general prediction that the deal would lengthen the amount of time it would take for Iran to obtain a nuclear weapon from a few months to fifteen years, claiming, “Some have expressed concern that the deal will free Iran to develop nuclear weapons without constraint after ten years; in contrast, we find that the deal includes important long-term verification procedures that last until 2040, and others that last indefinitely under the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons Treaty (NPT) and its Additional Protocol.” This assertion states that it would greatly increase the amount of time it would take for Iran to achieve nuclear weapons, extending the amount of time it would take from “a few weeks” to approximately 24 years.

Responding to criticism that a set date permitting Iran to revive its work on centrifuges legitimizes Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons, John Kerry stated, “The international community is not telling Iran that it can’t have a nuclear weapon for 15 years; we are telling Iran that it can’t have a nuclear weapon, period.” He continued his assertions, declaring, “There is no magic moment–fifteen, twenty or twenty-five years from now–when Iran will suddenly get a pass from the mandates of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. In fact, this agreement does the exact opposite, as under IAEA safeguards, Iran is prohibited from ever pursuing a nuclear weapon.”

When it comes to lifting sanctions, the deal provides a few requirements for that to be achieved. If Iran adheres itself to the principles mandated within the deal, such as ending its nuclear weapon program and permitting international investigations to review compliance, then sanctions, including those on the energy and finance industries, shall be lifted. The elimination of sanctions played an instrumental yet ambiguous role in the deal; Iran desires to exploit nationalistic and anti-American sentiment as a result of these sanctions, yet wishes to rid them as well since they crippled the Iran economy. According to Ms. Sabrina M. Peterson, managing editor of the International Affairs Review, because “80 percent of the Iran’s public revenue revolves around oil” and “seeks American currency due to the destabilization of the rial,” the sanctions on its energy and finance sectors deteriorated the economic situation, forcing Iran to negotiate with the P5+1.

In exchange for lifting sanctions, Iran would end its nuclear weapon program and permit international investigations to review compliance. The deal mandates that Iran must fulfill various principles of the accord, such as eliminating many nuclear centrifuges, thus expunging their militaristic capabilities, in order for the sanctions to be removed. However, the accord anticipates any possible trickeries committed by Iran, containing “snapback” sanctions if a panel of nations should detect Iranian cheating.

Republicans have opposed the lifting of sanctions on two grounds: sanctions shouldn’t be lifted, since then Iran could further fund terrorist groups and it would fail to punish the Iranian government for holding Americans hostage, and that the lifting of sanctions should’ve been used to gain better results for America and Israel, since the sanctions should’ve been used to force Iran into accepting a “better deal.”

Sen. Ted Cruz claimed that if America lifted sanctions, America would become “the world’s leading financier of radical Islamic terrorism.” Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, Republican presidential candidate, mirrored his sentiment. “The reported details of the Iran deal include significant concessions to a nation whose leaders call for death to America and the destruction of Israel,” he said. “Today, the Obama administration has agreed to remove U.S. and international sanctions.”

Secretary Kerry opposed these stances. “There are some who point to sanctions relief as grounds to oppose the agreement, and that logic is faulty for several reasons,” he asserted. “The most important is that–absent new violations by Iran–the sanctions will erode regardless of what we do. It is an illusion for members of Congress to think that they can vote this plan down and still persuade countries like China, Japan, South Korea, Turkey and India–Iran’s major oil customers–to continue supporting sanctions that are costing them billions of dollars each year.”

Elaborating further upon why America maintaining sanctions on the financial sector wouldn’t be effective, he added, “And don’t forget that the money that has been locked up as the result of sanctions is not sitting in some American bank, under U.S. control. The money is frozen and is being held in escrow by countries with which Iran has had commercial dealings.”

However, Secretary Kerry did not address the criticisms regarding funding for terrorism. Indeed, the deal doesn’t outline any official punishments regarding Iran funding terrorist organizations, nor does it have any guidelines ensuring that the funds they achieve through the lifting of sanctions won’t be used to fund terrorist organizations. It also doesn’t mention any instructions relating to the American officials held hostage by the Iranian government.

The last dominant issue that the deal covers is investigations ensuring compliance. The full text of the Iran nuclear deal decrees that continuous surveillance at enrichment and centrifuge production and storage shall be permitted, and that the IAEA has the right to visit suspicious sites “anywhere in the country,” giving Iran 24 days to comply with the request. Certain provisions will last for 20 or 25 years, and others will last permanently, according to Secretary Kerry.

Many Republicans have criticized the requirement that allows Iran 24 days before any investigation takes place. Dr. Ben Carson, Republican presidential candidate, claimed, “If we want to inspect something, it has to go through a committee on which Iranians sit, and on which the Russians sit.” Many assert that this timeframe provides Iran the opportunity to conceal any evidence of the purifying of nuclear materials for anything besides medical isotopes.

Secretary Kerry protests these beliefs. “In truth, there is so way, in 24 days–or 24 months, for that matter–to destroy all evidence that an illegal activity has been taking place,” Secretary Kerry argued. “Because of the nature of fissile materials and their relevant precursors, you can’t eliminate the evidence by shoving it under a mattress, flushing it down the toilet or carting it off in the middle of the night. The materials may go, but the telltale traces remain year after year after year.”

Corroborating Secretary Kerry’s claims, Mr. Ernest Moniz, former head of the MIT nuclear physics department and current secretary of energy, in a humorous statement on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, said, “There have been allusions to throwing drugs down the toilet. It doesn’t work that way, the nuclear material.”

The same 24 leading scientists from the letter also praised the inspections guidelines. “The 24-day cap on any delay to access is unprecedented, and will allow effective challenge inspection for the suspected activities of greatest concern: clandestine enrichment, construction of reprocessing or reconversion facilities and implosion tests using uranium,” they said.

However, they also advised caution, recommending other steps that could be taken to strengthen the existing guidelines. “We do believe that it would be valuable to strengthen these durable international institutions,” they stated. “We recommend that your team work with the IAEA to gain agreement to implement some of the key innovations included in the JCPOA into existing safeguard agreements.”

Beyond the differing ideas on how to prevent Iran from producing a nuclear weapon, both the Republicans and Democrats have underlying motives that they wish to achieve.

Republicans may be aiming to exert an image of American authority as well as secure a new voting bloc.

Following conservative ideology, conservatives may be rejecting the deal because they view it as an act of America kowtowing to one of its enemies. Explaining why Republicans view the deal as an act of appeasement, Ms. Susan Lueders, government teacher, stated, “The Republicans believe that the bill is too soft on Iran. They believe that it’s causing the United States to appear weak and ineffective, and that it’s setting America up for failure.”

This is not only an issue of superpower status, but also of national security. According to a 2015 Pew Research Center report, “76 percent of Americans rank terrorism as a top priority.” Because of Iran’s status as an enemy of America, Republicans may believe that the deal may strengthen Iran to the point of posing a threat to America.

In addition, Republicans may be attempting to side with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to appeal to Jewish voters. If the GOP hopes to win the presidency, both in the present and in the future, they need to create a long-term strategy of building a sustainable national coalition. A common criticism of the GOP is that it is a party catered towards old white men, and that the policies they create harm women and racial minorities.

This is a damaging sentiment for the Republican party, since a recent study states that, to win the presidential election, the GOP will need to achieve at least 40 percent of the Latino vote. Considering that 71 percent of Latinos voted for Pres. Obama while 27 percent voted for Mr. Mitt Romney in the 2012 presidential elections, that means that the GOP will need to convince at least 13 percent of Latinos to change their vote.

In the current environment of the presidential campaign, gaining that 13 percent might be even more difficult than before. Mr. Donald Trump, the current leader in the polls for the Republican presidential nomination, with his inflammatory comments describing Mexicans as “drug dealers” and “rapists,” paints the Republican Party as virulently anti-Latino to many. According to a Marist poll, “70 percent [of Latinos] had a ‘somewhat negative’ or ‘very negative’ view of Mr. Trump.”

During a time when the Latino vote is becoming increasingly crucial, Mr. Trump’s remarks will spur Latinos to the polls in record numbers, according to U.S. Hispanic Chamber of Commerce President and CEO Javier Palomarez. With many Latinos holding an increasingly negative view of the Republican Party as a result of Mr. Trump’s supposed anti-Latino views, it is highly likely that they will vote for the Democratic candidate instead, lessening the Republicans’ chances of winning the presidential election.

To compensate for their predicted loss in the Latino vote, it is highly likely that the Republican Party will attempt to reach out to Jewish voters as they did to Catholic voters in the past, attempting to convince this traditionally liberal-leaning group to vote for Republicans through their opposition to the controversial Iran deal.

The Jewish-American community has been divided on the deal. Opposing the deal, influential Israeli lobbying forces, such as the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, spent tens of millions of dollars to prevent the accord, and PM Netanyahu condemned the bill, stating that Iranian threats to destroy Israel have been met by “utter silence, deafening silence.”

Invigorated by PM Netanyahu’s claims, older, more orthodox U.S. Jews have rallied behind the Republicans with the belief that protecting Israel is imperative. This reflects the priorities of many Jews since, according to a Pew Research Center survey, “53 percent of American Jews over the age of 65 equate caring about Israel with their Jewish identity.” By opposing the Iran deal, the Republicans cater to older American Jews, an influential voting bloc.

However, this approach would fail to appeal to the younger generation, since younger U.S. Jews tend to be more critical towards Israel’s stance on the Iran nuclear deal, largely unaffected by PM Netanyahu’s claims. A Pew Research Center survey reported that “only a third of [American Jews] under 30 equate caring about Israel with their Jewish identity,” explaining the relatively stalwart support for the deal despite PM Netanyahu’s urging, since many of them wouldn’t feel personally threatened by alleged threats imposed against Israel by the bill, thus aligning with the Democrats on the issue.

Democrats also possess ulterior motives towards their stance on the deal, navigating a tenuous limbo between appeasing the growing antiwar sentiment on the left, maintaining an image of America as a superpower and effectively combatting ISIS.

Among the general public, and especially among liberal voters, America taking military action is being seen as an increasingly unpopular move. According to a 2013 Gallup poll, weary from decades-spanning overseas conflicts, 68 percent of Americans oppose using military action “to attempt to end conflicts” if “all economic and diplomatic efforts fail.”

Posing a problem to the growing anti-war movement, PM Netanyahu likely plans to launch a preemptive Israeli strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities, an attack that would trigger a war between Israel and Iran, which would force America to enter the military conflict due to the American-Israeli mutual defense treaty.

This action would prove problematic to Democratic interests. With the Democratic Party aiming to win the control of Congress back from Republicans, Democratic politicians must entice these voters with the promise of no more wars, spurring them to attempt to prevent a war from arising between Israel and Iran.

Likewise, Democrats may be attempting to cater to the growing number of Americans concerned with America being a top power, especially with the perceived looming threat of China. A June Gallup poll stated that majorities or pluralities in 27 of 40 countries surveyed say that China “will eventually replace” or “has already replaced” America as the preeminent superpower. Revealing the increasing unease over the notion of China’s increasing power, a March Gallup poll asserted that 49% of Americans believe that keeping America as the sole superpower is very important, an enlargement of previous years’ results.

Regardless of whether America rejected the deal or not, the other P5+1 nations planned to drop sanctions against Iran, which would have reduced the opposition towards Iran from a multilateral effort to a unilateral one. If this situation had occurred, America would have appeared weak since it would have appeared to many that they were unable to control even their greatest allies and partners during a time of dire crisis. Aiming to secure the image of America as a world power and lure in voters concerned with preserving America’s status as a world power, Democrats may have planned to drop sanctions now so that it appears that the other P5+1 nations have followed America’s example, perhaps strengthening the image of America as an international leader.

Lastly, Democrats may be attempting to find the best way to counter ISIS while still attracting anti-war voters. Showcasing the overall support of America’s efforts against ISIS, a July Pew Research Center report revealed that 63 percent of Americans support action against ISIS. This support drives many Democrats to continue efforts to annihilate ISIS; however, they still have to balance these efforts with the increasing number of Americans who disapprove of military intervention.

To appease both perspectives, Democrats’ tactics may involve providing assistance to its Middle Eastern allies against ISIS rather than direct military support. Nevertheless, the situation in ISIS has been complex, defined by an interplay of politics. While Israel has the strongest military in the Middle East, they are unable to attack ISIS since, due to their reviled status amongst most Middle Eastern nations, it would cause the other nations in the Middle East to terminate military action against the terrorist organization. Unwilling to allow Iran, a nation who chants “Death to America,” to become the main opposition towards ISIS due to fears that they will gain much influence over the nations they liberated, America has placed its hopes in Iraq as the primary force against ISIS.

Damaging those hopes, though, is the growing civil war in Iraq, which has greatly minimized Iraq’s ability to be a united front against ISIS due to conflicts from within. With the assistance of other nations, including America and some European nations, there are two main forces against ISIS in the region: the Kurds and the Iranians. Unfortunately, providing the Kurds with aid proves its own obstacles and difficulties.

Although the Kurdistan’s Working Party (PKK) is designated as one of the most effective forces against ISIS, the US is unable to support them officially. If the US government armed the Kurds, as Ms. Fiorina suggested, then they would deeply damage relations with Turkey, one of our most crucial allies in the Middle East as well as a NATO ally, because the Turks and the Kurds have contentious relations due to the PKK waging war against Turkey for independence, with both of them are currently battling one another while still confronting ISIS. Forced to reconcile with both of these opposing forces, the American government must discover methods to both equip the Kurds with arms and prevent strained ties with Turkey as a result of arming them.

Further complicating our attempts to find forces against ISIS that won’t damage our relationship with allies, Syria has completely failed as a potential option. President Barack Obama abandoned his $500 million campaign to train thousands of Syrian fighters to fight ISIS in face of its failure, claiming that they will use the money to provide ammunition and arms to groups already engaged in battle instead. Embroiled in a civil war that forced millions of Syrians to flee their homes, the civil war between dictator President Bashar al-Assad’s army and rebel forces took a turn for the worse when Russian President Vladimir Putin decided to bomb Syria in a move that shocked American officials.

Although the Kremlin professed that they entered Syria to combat ISIS, in reality, the bombs were targeting areas populated by insurgent forces, allowing ISIS to gain even greater control over the area.

Within this complicated geopolitical environment, one where enemies are elevated to the status of situational allies and one where allies combat each other, it is likely that the Democrats aimed to keep their options open in regards to forces against ISIS. This desire likely influenced the conception of the Iran nuclear deal, as America cannot risk completely alienating or ruining Iran without eliminating one of ISIS’s most effective enemies, thus causing them to be more willing to compromise than they usually might be.

Of course, the underlying motives may be partisan chicanery as well, with both sides maintaining their stance due to the political party that proposed the idea. “[Politicians] don’t see things in a non-partisan way; they’re framing it in a bipartisan way,” Ms. Lueders said. “Meaning that if a Democratic president proposed it, the Republicans would oppose it. Likewise, if a Republican president such as, say, President George W. Bush proposed the deal, the Democrats would oppose it.”

Elaborating further, Ms. Lueders claimed, “One reason that [the Democrats] are supporting the deal is that they’re supporting the president and John Kerry. The Republicans could be opposing it for the same reasons, hoping to support their party.”

Overall, regardless of the politicians’ motivations and stated intentions, the Iran nuclear deal will impact politics on a large scale.

Addressing the questions currently facing the deal, Ms. Lueders said, “Politically, on the world stage, it’s showing how much the power the United States has or doesn’t have. An ongoing debate might be whether this deal showed that we were leading the charge or if it showed that we were weak.”

Continuing further, Ms. Lueders stated, “Are we having to take a step back to make peace right now, or are we taking a hardline stance? WIll it harm us in the future by removing our leverage? Will it destabilize the Middle East? What will it do to our relationship with Israel, a historically maverick country that frequently makes us nervous? Only time will tell.”

Madina Jenks is a senior and a new copy editor for Highlander Publications. As a copy editor, her jobs are pretty simple: write and help others write....