Smartphones in Schools: Benefit or Distraction

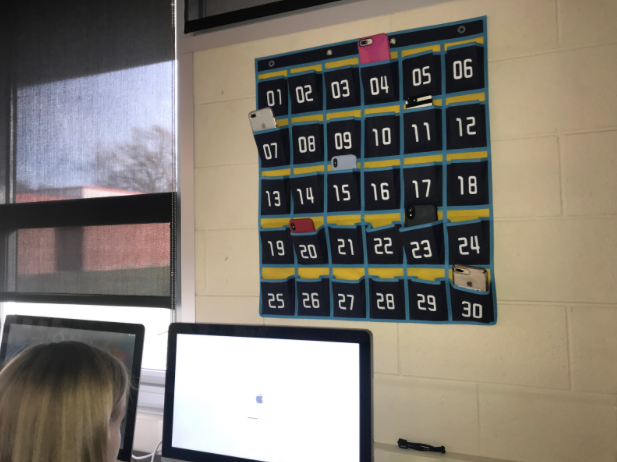

Claire Baden, sophomore, works on a computer in class next to a mostly empty phone pocket.

Smartphone use in schools is an issue being debated all over the world. France has just implemented a ban on smartphones in schools and other countries are expected to follow their lead, except the US.

There is one main reason for these changes: safety. While European countries have little to no gun violence in schools, the US has a significant amount each year. According to New York Times writers Alissa J. Rubin and Elian Peltier American students, smartphones feel like a necessity for armed intruder events. This is causing schools across the US to come up with creative solutions for the continuous rise of smartphone use in classrooms.

A study conducted by the Pew Research Center reports that, 73% of teens own a smartphone and that 97% of phone uses text every day. American teens on average sent 60 texts a day in 2009, by 2015 this number jumped to 167 texts a day.

According to Amanda Lenhart, a Pew Researcher, “92% of teens report going online daily—including 24% who say they go online ‘almost constantly.”

According to Oxford Learning, students check their phones in class an average of more than 11 times. In a study by Jeffrey H. Kuznekoff, Scott Titsworth and the American Psychological Association, students who were not using their mobile phones wrote down 62% more information in their notes, were able to recall more detailed information from the class, and took more detailed notes.

The students also scored a full letter grade and a half higher on a multiple choice test than the students who were using their mobile phones instead of paying attention to the class.

Rising phone usage prompted Principal Brett Bowers to implement a new phone policy during the 2017-2018 school year. The policy included phone pockets in every classroom and detentions for phone abusers. It also included a ban on smartphone use in the hallways and bathrooms during an ongoing class period.

Last year, after having a phone confiscated three times, violating students would receive a half day in-school suspension per Homestead school policy. This year though, after three a student will lose their privilege to exempt an exam.

Bowers said that creating the right policy is hard and is still an issue that he hopes to continue to address in the future.

“I think we still have not fully hit our mark with the management of cell phones. They are prevalent, and we want to honor the fact that they’re an important piece of technology,” Bowers said.

The largest issue with the phone policy, according to Bowers, is the inconsistency between each individual classroom. This is an issue that affects both teacher and students.

“I think [cell phone use] is a question of accountability and enforcement and expectations, where we still need to make sure that we are consistent from classroom to classroom.. don’t know that that’s a change; it’s just refinement we need to be better at what we said we’re doing,” Bowers said.

Mrs. Kristi Ribar, a teacher who has been at Homestead for 24 years, has seen the changes that come with all of the many different phone policies at Homestead over the past two decades.

“Yes, [there was less phone use] for a while, but then it kind of tapers off, and people go ‘well maybe I’ll still try having my phone out,’” Ribar said.

Ribar explained that the smartphone policy works well when it’s new, and teachers and students alike make more of a effort to follow the new rules. Yet as many observe now in classes most phone pockets are left empty.

Because of the inconsistencies among classes, Ari Halaska, sophomore, finds the phone policy to be unfair.

“I think the school has not made a clear system of what to do when a student is on their phone,. Yes they say ‘if you see it it’s a detention’ but some teachers or willing to give students more than one chance if their phone is out,” Halaska said.

Yet, smartphones aren’t all bad, according to Bowers. Smartphones can be an important part to students’ learning.

“When they’re used for educational purposes, they are a really powerful tool. You have, at your fingertips access to so much information and so many tools…but there is a difference between it being a tool and being a distraction,” Bowers said.

Susan Sawyer, a professor of adolescent health and pediatrician, believes that there is no need for a ban on smartphones in schools.

“A particular benefit of mobile phones is they can provide access to therapeutic intentions for distressed young people while they are at school…[also]the emergence of crisis text lines means adolescents can access text messaging support in real time, an approach that many find more accessible than telephone support, let alone face-to-face support, even with trained professionals at schools,” Sawyer said.

Claudia Chedid, sophomore, also thinks smartphones can have benefits to students in moderate uses.

“I think phones allow people to get a mental break during school, which is helpful for a lot of students especially since classes can be overwhelming and stressful,” Chedid said.

While the current smartphone policy has room for improvement, it’s important to remember that the main goal is to further students’ opportunities in school and beyond.

According to Bowers, there are no major changes to the policy coming in the near future.

Caroline Weir is a sophomore at Homestead High School. In the fall she enjoys running on the cross country team and in the spring she plays varsity lacrosse....