Coronavirus: Life in the quarantined Lombardy region

Chiara Guadagna, an 18 year old living in the Lombardy region of Italy at the height on the coronavirus, explains her life on lockdown.

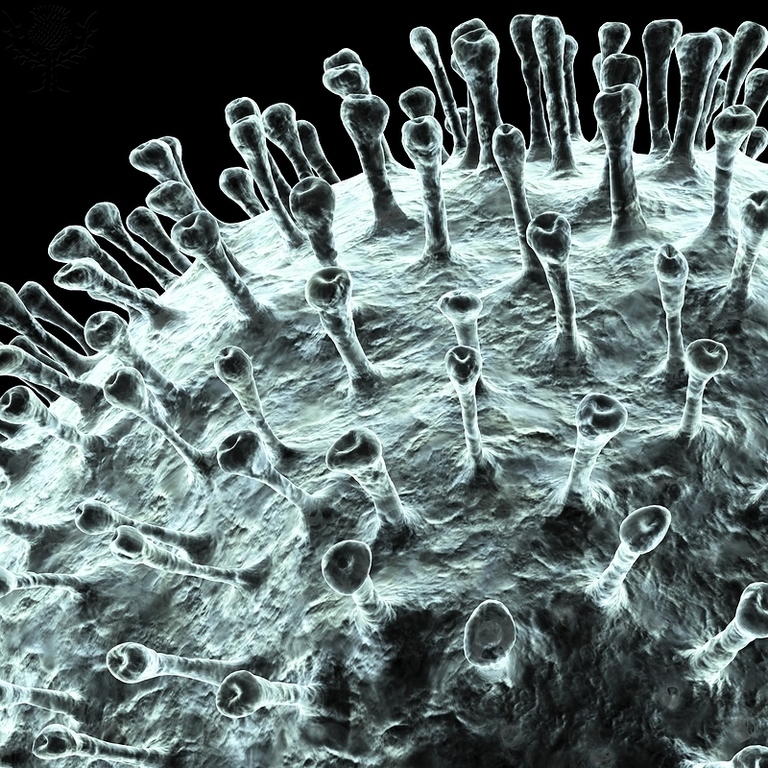

At the top of all recent news headlines across the globe is the coronavirus. The virus, which primarily infects the respiratory system and has the symptoms of a common cold, began in Wuhan, China and has now spread internationally. It has since been deemed “COVID-19,” a severe and sometimes fatal virus.

After China, Italy has the highest death toll of almost 400 people as of March 9. The disease has mostly affected the northern region, near cities like Milan and Venice. With almost 8,000 confirmed cases and rising health concerns, Italy has called for lockdown and quarantine of the entire country. This means nobody is able to enter or leave, except tourists.

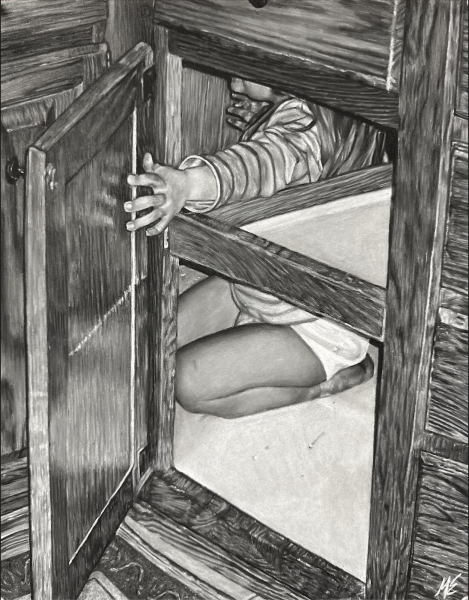

For many of us, it is hard to imagine living in quarantine. While the impact of the coronavirus has hit the United States, we have not yet been put under extreme conditions to control it. For others, however, quarantine is a harsh reality.

Chiara Guadagna a student in Italy lives in the Lombardy region, about 100 miles southeast of Milan.

Having been out of high school since Feb. 26 for quarantine, she does not plan to return until the quarantine is over on April 3 although it could be extended. All her classes have been through Skype with her teachers as they continue to prepare for exams, and she still receives homework.

“We have a video chat with our teacher at a specific time and then we do our lessons. So basically we turn our microphones off and the teacher explains the lesson. If we do have questions or we don’t understand we can type it on the chat and then, as the teacher is constantly looking at it, she or he will explain what we didn’t understand again and so on,” Guadagna explained.

While not in school, there is little to do. Besides her school, all her local gyms, bars, clubs and theaters have been closed. Restaurants are only open for take out, but supermarkets remain crowded. “People are so afraid of being left with nothing that they go to supermarkets to buy as much stuff as they can and sometimes they can get dangerous,” Guadagna said.

Residents leaving their house must wear a mask, gloves and stay a meter apart from everyone.

With everything being shut down, Guadagna fills her time with school, family time and occasionally hanging out with friends. “I barely do anything. We spend the whole day at home, watching TV, making breakfast, lunch and dinner and the day after we repeat the same routine,” Guadagna said.

Living with her parents and one grandmother, Guadagna’s biggest concern is the elderly people in her family. “I am really worried about my grandmothers and also for my aunt because she has a very bad disease, and if she gets the virus I don’t think she will be able to be cured,” Guadagna said.

“My two grandmothers do not go out at all in order to avoid any sort of contact, and they are really afraid,” Guadagna said. She went on to explain that her small Italian village of 700 people is a majority elderly population.

However, she also describes how some people are not as worried about the virus. “On the other hand a lot of people do not consider this virus deadly and they don’t take precautions. I think this is one of the reasons why the virus spread so fast, as the first cases were in Milan and in less than a few days it arrived here,” Guadagna said.

As for Guadagna and her family, none of them have been personally affected, but she does know of some people who have. “The pastor of the church I used to go to [has been infected]. He was present during my baptism, communion and confirmation,” Guadagna said.

Guadagna also claims that medical help is difficult to find, and there are a limited number of doctors. With a finite number of professionals available, she explains that doctors are forced to choose who they can and cannot treat. “There are so many infected that doctors have to decide who gets treatment and who doesn’t,” Guadagna said.

To cope with this issue she says, “[Today] a few volunteers made up a sort of tent outside in order to test people to see if they had the virus or not. Unfortunately, the outcome was dramatic as loads and loads of people have been diagnosed with the virus and forced into quarantine,” Guadagna said.

With numbers increasing every day, the use of the quarantine hopes to restrict travel and reduce the risk of an increase in cases. While Guadagna’s quarantine experience in Italy shines a light on the experience of one family, her case is not the same for everyone. “Of course I am scared, but I think that overreacting will not change my situation. I know that if I follow the rules I will stay safe and I will keep my family safe as well,” Guadagna said.

Hannah Kennedy is a senior at Homestead and serves as editor in chief of Highlander Publications. She is going to study journalism in college at the University...

Karen Adams • Mar 10, 2020 at 3:38 pm

You gave the harsh reality of a quarantine and made it personal. Great writing!