Making homework meaningful

Students have argued that homework is useful when they are struggling.

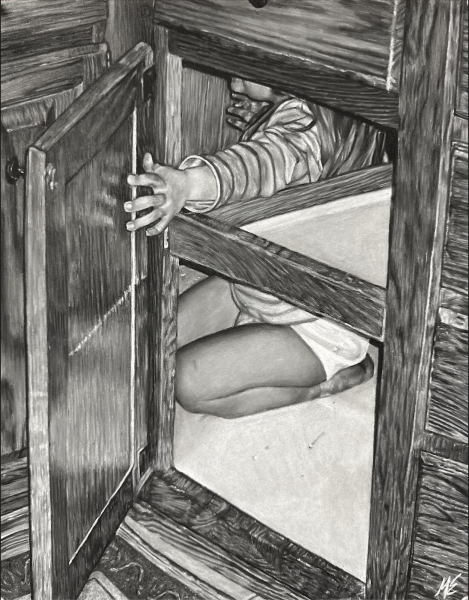

As the clock ticks away, a student holds his head in his hands, wracking his brain for the correct answer. I really wish I did the homework.

Homework, defined by Merriam-Webster Dictionary, is work that a student is given to do at home. At Homestead High School, homework is extremely common. It is given for almost every class, on average, for about an hour of homework for every hour of class.

Students are at school for approximately eight hours, so many feel as though they should not be assigned more work to do at home. Students argue that teachers do not take into consideration the sports, clubs and other extra-curriculars that students have when they are assigning homework, while other students say that school should always come first, and that they should do homework first, then use the extra time to enjoy doing other activities.

Mr. Joe Ciurlik, American Studies and AVID teacher, explains that teachers do think about how much homework they assign and that they do take into account the number of extra-curriculars that students participate in. Ciurlik said, “We’re mindful of what our students are involved in.”

Mr. Ciurlik describes that students also need to understand that they are a student first, and an athlete second. Mr. Ciurlik said, “I can think of less than 10 kids in the North Shore Conference who make a living doing their extra-curricular.” He added, “What I’m saying is, students need to know where the priorities are.”

Homework can prove to be very beneficial, when it is used correctly. Teachers have seen improvements in test scores when when they assign meaningful homework that helps students practice the skills that they have learned in class. Herbert J. Walberg, a professor emeritus of education at the University of Illinois and a fellow at the conservative Hoover Institution, said, “‘More than 100 studies indicate that the more you study the more you learn.’”

Kathleen Cullen, senior, agreed that homework helps students learn, but can be too much on certain occasions. Cullen said, “I think homework is a necessary evil, but sometimes the amount that we get is ridiculous.”

Some opponents of homework argue that the homework student receive is not beneficial at all. Research proves that American high school students eventually fall behind in areas like math and science when tested against students in other areas of the world.

Patrick Marshall, author of the article “Homework Debate,” found that “American fourth-graders scored above the international average in math and science, and eighth-graders scored above the international average in science. But eighth-graders fell below the average in mathematics, and seniors scored among the lowest in both subjects.”

American students start out ahead, as evidenced by the above-average scores of fourth graders when tested in math. However, Americans eventually fall behind in areas like math and science. Walberg, “largely blames the relatively small amount of time American students spend studying, and says U.S. students simply aren’t challenged the way European and Asian students are.”

Most school communities, however, are divided on the amount and purpose of homework. Marshall said that, “a homework load that may overwhelm one student may be easily manageable for another.”

Additionally, “many schools confuse rigor with load,” according to Denise Clark Pope, a senior lecturer at the Stanford University School of Education who has become a leading national expert on the causes of stress for high school student. Just because a teacher assigns homework does not mean that those will see the benefits of a rigorous workload.

Alan Lesgold, dean of the school of education at the University of Pittsburgh, summarized that the, “Bottom line is that it [quality of the homework] depends heavily on the quality of the assignment, the extent of quick feedback, whether the student is motivated to do it, and possibly whether there is support outside of school, especially for the kind of big projects that can be demanding of a lot of parent time that may be less available when the parents are working multiple minimum-wage jobs.”

In Sarah Boesveld’s article, “No More Homework, she tells the story of David Martin’s high school math class in Red Deer, Atlanta. It was just like every other class, but the dropout rate became around 40 percent, and Mr. Martin “knew something had to change” (Boesveld). Mr. Martin eliminated homework from his curriculum, and three years later, “Students work on one or two harder, critical-thinking problems per class and are encouraged to take their time and be creative. No work goes home” and the class dropout is now at 5 percent.

Along with overall disdain with homework, studies show that homework has many negative effects on students. Valerie Strauss writes in her article, “Homework Hurts High-Achieving Students,” “…a heavy homework load negatively impacts the lives of high school students in upper middle-class communities, resulting in excess stress, physical problems and little or no time for leisure.”

Hannah O'Leary a senior who finds herself as the editor-in-chief of Highlander Publications. Hannah loves designing magazine spreads, but finds that she...