Skirts, stilettos and sandwiches: How the cinema perpetuates sexism

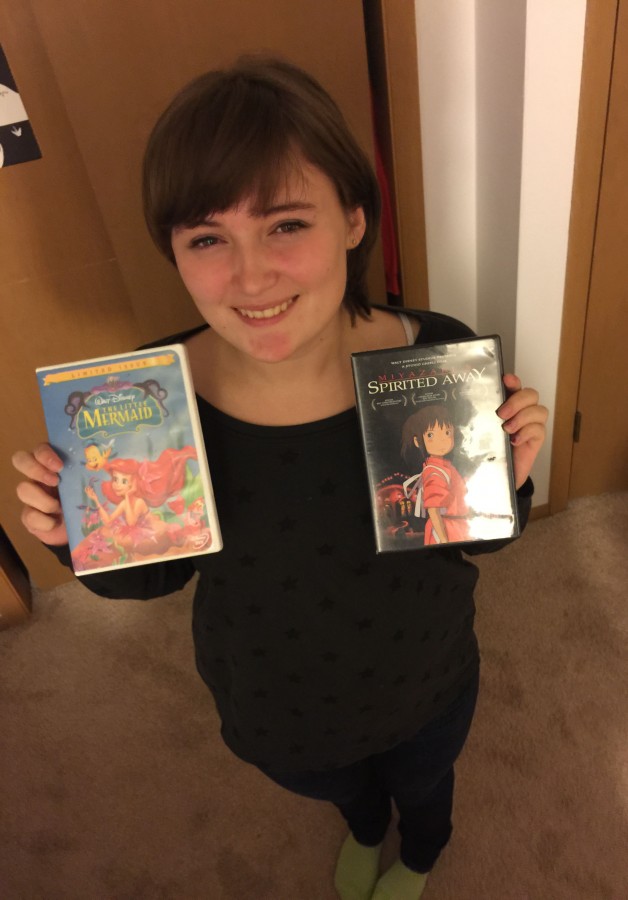

Sara Imbrie, junior, poses with copies of two movies that she adores: The Little Mermaid and Spirited Away. Growing up, she watched these films with delight numerous times, having really related to the main heroines in each. “I feel like these girls are good role models,” she explained.

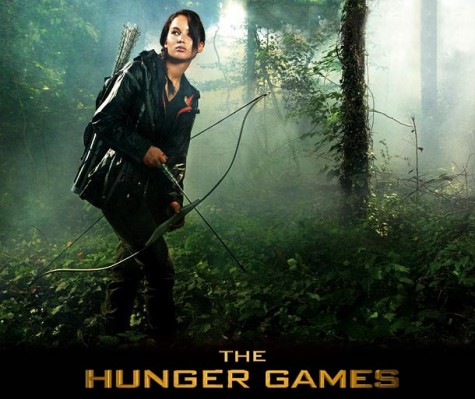

Thwack, thwack, thwack! Each of cinema darling Katniss Everdeen’s arrows hit their mark, and as the stoic heroine poses triumphantly, a deluge of lights and cameras sweep over her in a grandiose panorama shot to express her glory. Shepherding in a new age of films and other media led by powerful female figures, Katniss was one of the figureheads of this new movement, dominating both the minds of the human population as well as the box office.

Following in her lead, female-led movies have flooded box offices over the past few years. Love it or hate it, according to the International Business Times, Frozen, headed by female protagonists Elsa and Anna, proved its box office merits by earning $1.0724 billion, and that does not even account for the massive revenue it churns out through its merchandise sales. Similarly, the film Divergent, driven by the heroine Beatrice Prior, churned out nearly $300 million in the box office.

Also, Bridesmaids, a breakthrough film with an all-female cast, showed that women could be just as hilarious as men and was a smash hit at the box office, grossing almost $300 million worldwide. And Mamma Mia, the best-selling musical film in history, gained more than $602 million. Clearly, the demand for a female-led film is astronomical.

So that leads into the question, why has Hollywood not made more female-led films sooner? In order to explain this, Marcus James Dixon of the Gold Derby, mirroring the sentiments of most Hollywood executives, argues that female-led films generate less revenue. However, according to Box Office Mojo, the movies Hunger Games: Catching Fire, Frozen and Gravity, each of them starring females as the main characters, were among the top ten highest-grossing films in the year of 2013, respectively earning $424 million, $400 million and $274 million domestically.

This spade of high-grossing female-led films is not a new phenomenon either. Mr. William Woessner, Homestead psychologist, states, “Over the years, there were many movies with strong female-led casts, ensemble or not, that were extremely successful, such as The Color Purple, Fried Green Tomatoes and Sophie’s Choice. None were flops or bombs, especially when you consider what their production costs were, and many resulted in Oscar nominations, Oscar wins, or Screen Guild Association Awards.” Clearly, female-led movies have a history of being successful.

Because of that, there is one thing that can be concluded; our cinema is sexist, and its effects are often insidious and pervasive on American society. As a whole, the cinema fails to represent women properly, failing to provide their female audience with neither quantity nor quality.

The most visible form of the sexism inherent in our cinema is the disproportionate lack of female characters compared to their male counterparts. Martha M. Lauzen, Ph.D., stated, “Females comprised 15 percent of protagonists, 29 percent of major characters, and 30 percent of all speaking characters.” When women account for less than one-half of any character type, one can already see just where the inequalities begin.

Another major problem when it comes to the sexism in the cinema is the propagation of gender roles. Oftentimes, the gender roles that the cinema perpetuates are absolutely toxic, harming both men and women, but especially women through their men-oriented, submissive portrayals.

An indicator of the intrinsic sexism within films is evident in the results of the Bechdel Test. The Bechdel Test is a test measuring the successfulness of female characterization in a film based on three major criteria: a film has to have at least two women in it, the women must talk with each other, and their conversation has to be about something besides a man. While the test admittedly has its flaws, it is nonetheless considered the most effective test to examine if a film passes the bare minimum in its depiction of female characters.

While this set of expectations might seem remarkably easy to accomplish for any film, a shocking number of movies fail to achieve this. According to the Bechdel Test database, 74 out of the 161, or nearly one-half, of the films released in 2014 failed the Bechdel Test. While these absurd statistics seem like they have come straight out of the 1950s, they in fact come from the modern day and age of 2014, showing that the cinema still has some major progression to accomplish in terms of female representation, especially when it comes to establishing female characters as their own characters rather than as an attachment to a male character.

In addition, Ms. Lauzen also stated, “Female characters were more likely than males to have an identifiable marital status, a substantially larger portion of male than female characters were seen in their work setting actually working (61 percent vs. 40 percent) and only 8 percent of women were presented as leaders compared to the 21 percent of males who were.” This reinforces the notion that what is most important about females is their relations to males, as well as the idea that a woman’s professional life does not matter as much as that of a man’s and that women just are not as capable of leadership as men are.

Yet another major problem with how women are portrayed by the cinema is through their over-sexualization of the female form. According to a new study by USC Annenberg researchers Stacy Smith, Marc Choueiti and Stephanie Gall, “33.8 percent of female teen characters were seen in sexy clothing, and 28.2 percent were shown with exposed skin in the cleavage, midriff or upper thigh regions, while only five percent of male teens were shown in sexy clothing and only 11.2 percent were showing skin.” This proves that there is indeed a bias in which gender gets more sexualized, and that it is females, especially young females, those who are within the median ages of many girls who attend Homestead, who bear the brunt of this form of objectification, emphasizing the idea that females serve an inherent role in society as eye-candy for the males.

While some may argue that there is an inherent disconnect between the media and reality, that what flits across our screens does not affect people at all, Mr. Woessner heartily disagrees. “[The cinema] casts women most often in subservient roles, as less powerful than males, in more need of being rescued and as less independent, to the point that you can even put the scale between dependence and independence on a male-female scale,” Mr. Woessner explained. “[Because the cinema] serves to reflect society as a whole, these depictions of women shape our beliefs on what women are supposed to be, how they are supposed to behave, and how we are meant to treat them.”

Another medium in which movies spreads their sexism and gender roles is within the cinematic technique known as the male gaze. The male gaze is a technique in which the camera pans over the body of a woman in a way that is specifically meant to titillate the male audience. Common ways of doing so are lingering camera shots on typically sexualized portions of a female’s body, such as the breasts, legs and posterior, adjusting the lighting in order to make the woman appear softer and more appealing and lovingly lingering on women in typically “female” scenarios, such as cooking a meal in the kitchen or caring for her husband.

According to Lauren Mulvey, author of the article “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” utilizing this kind of technique causes women to become “the bearer of meaning, not maker of meaning.” Explaining this further, she said that because women, unlike males, seldom find themselves in the role of the spectator, or in the role of control, they have little access to the camera and/or control of the narrative.

This means that, due to this exclusive male control of the medium of film, any pleasure derived watching the film comes from a male context, so if women want to gain that same sort of pleasure, they themselves have to assume the male gaze and accept themselves and other women as objects, which leads to the further reinforcement of the objectification of women.

This type of objectification has further damaging effects on women than what is immediately apparent. Mr. Woessner said, “[For females], there is an absence of an equivalent for the [male gaze], so we’re promoting male superiority, male dominance and the patriarchy by casting females in softer and more sexual lights and in more submissive roles.”

Pointing out the effects this has on young women, Mr. Woessner explained, “It’s not healthy for girls because when girls are bombarded with these images, then these types of sexist expectations become a societal norm, and girls are taught to be submissive and quiet. In the classroom, teachers tend to call more on boys than girls since girls are taught to be more quiet, and when boys debate with girls, it is generally the girl who gives up and capitulates because [of how she is taught to behave.]”

Amelia Stastney, junior, described her own feelings, saying, “Women are frequently shown to be second-hand [sidekicks], side plots, distractions or comic relief to the main male character, which is why people make such a big deal about strong female characters rather than strong male characters, since it’s assumed that all male characters will be strong, which really points out how sexist it all is.”

While some may argue that the cinema has a limited role in our cultural perceptions, it is obvious that the reality is the opposite, as the media’s messages influence every portion of our culture. “You can’t get away from [the cinema’s messages]; some are blatant and some are subtle, but when you’re surrounded by them, you cannot escape them,” Mr. Woessner said. “These types of images, perpetuated over and over again, later create a hegemonies–underlying assumptions we accept as truths or givens–that are frequently not questioned by society as a whole, and the cinema works to create those hegemonies about the role women play in our society and reinforce them.”

Knowing this, there is one question that remains; why should the average Homestead High School student care about the sexism that is depicted in the cinema? After all, this is Homestead, the school of equal opportunity and equality and as such should be free of any of those societal ills, so why should any member of the school care about the sexism that is prevalent in other areas of the world?

The answer is that Homestead, like other parts of the country, is not free of sexism or toxic gender roles. Mr. Woessner stated, “[Homestead is] a part of the larger culture, and therefore, we can’t escape society’s ills.”

Sarah Imbrie, junior, explained how she herself struggled from our society’s sexism, sharing, “Every day, I’m trying to combat the internalized sexism that I face.”

So, even if cinema isn’t the sole perpetrator in terms of reinforcing various sexist notions on women, we do have to acknowledge its massive role in strengthening these beliefs on society. And every student at Homestead, in order to avoid allowing these types of toxic ideas to infiltrate and poison our minds, should try to dissect what the cinema is trying to tell us in order to avoid the same types of damaging mindsets that plague the rest of American society.

Madina Jenks is a senior and a new copy editor for Highlander Publications. As a copy editor, her jobs are pretty simple: write and help others write....