How the ‘girlbosses’ fell from grace

What happens when your feminism is paper thin?

The word ‘girlboss’ is scattered throughout Tik Tok comments and Twitter think pieces alike. On the surface it’s a seemingly harmless phrase: one established to lift modern women up against the heavy weight of the patriarchy. But as time has gone by, it has become increasingly obvious that the saying is outdated and harmful to the ever-growing effort to make worldwide feminism more intersectional and not just a movement helmed by privileged women to benefit privileged women.

In a way, the ‘girlboss’ is simply another cliche trope that’s similar to the ones women have been dodging for decades. Instead of the doting, swing-dress donning wives and mothers who made up the picture-perfect images of the mid-20th-century, “girlbosses” are hard working ladies brimming with vivacity that are focused on climbing their respective professional ladders while wearing something simultaneously provocative and trendy — like a pink pussyhat.

The term ‘girlboss’ was popularized in 2014 by entrepreneur Sophia Amoruso when she made it the title of her memoir. The book went on to sell over half a million copies, spawn a multimedia company, and prompt the creation of countless items of merchandise that proudly presented its message. “Girlbossiness” initially proved itself to be something that wasn’t only uplifting but also wildly profitable, which can be a dangerous cultural mix.

Recently, questions have been raised about whether or not widely promoting a singular archetype is a good thing, especially during a time when freedom of expression is so encouraged and the idea that a person can be successfully put into a singular box has been disproven. All of this has effectively begun to crack the millennial pink candy coating that once covered the girlboss movement.

In 2016, The Wing, a female-focused coworking space, was founded to further “the advancement of women through community,” and it quickly took flight, raising over 117.5 million dollars in just two years according to Fast Company. Working women enthusiastically flocked to the Wing, and it amassed over 12,000 members and a waitlist of 9,000 wannabe winglets.

The Wing currently has almost half a million followers on Instagram and it presents itself on the app as a magical place. One where politicians like AOC and Kamala Harris can campaign, actresses like Jennifer Lawrence and Reese Witherspoon can promote their new projects, and working women can come together and support one another while attending fun events like ‘Camp No Man’s Land’. However, the Wing’s employees have told an entirely different story than that presented on the company’s fabulous social media feed.

In 2020 a New York Times expose entitled The Wing Is a Women’s Utopia. Unless You Work There was published, and it provided former Wing employees a platform to share confessions regarding the true nature of the seemingly peachy-keen company. “‘I was the connector, the friend, the therapist, the mother, the sister, the live-in coach,’ one former employee says. ‘I was treated like a human kitty-litter box.’ Another says: ‘We were ‘the help.’”

Three weeks prior to the release of the article, The Wing’s CEO Audrey Gelman conceded that she had made a few missteps in the running of her business, saying in a statement released by Fast Company that “We’re still sold a dazzlingly unrealistic image of a female leader—or in 2020, a girlboss. She raises capital without raising her voice. She has it all and does it all, without error. The myth doesn’t account for the reality that running a company is messy, terrifying, and often chaotic, especially in the early years.” Gelman went on to step down as the CEO of The Wing four months later.

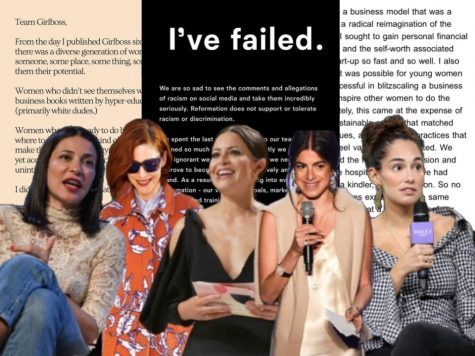

Around the same time, other female-founded companies like Reformation, Refinery29, and ManRepeller found themselves going down a similar track. The company’s employees spoke out about their toxic workplaces via social media, major publications wrote scathing exposes that cemented those grievances, and the founders of those companies swiftly stepped down.

Even Amoruso, girlboss of all girlbosses, found herself in a mess when her company—ironically not the one that’s named Girlboss—faced serious discriminatory allegations. According to The Hollywood Reporter, the clothing retailer Nasty Gal that brought Amoruso from rags to riches allegedly fired four of its female employees right before they went on maternity leave. Nasty Gal denied the claims, saying that they were “frivolous and without merit.”

It’s been a bit disheartening to watch the glossy and impressive leading ladies behind these companies fall from grace so publicly, even though they arguably deserve it. Each of these scandals have sort of felt like broken promises. These golden girlbosses spoke passionately about fostering an ethical workplace culture that fell in line with the third wave of feminism that was rolling in, but ultimately weren’t able to practice what they preached while keeping their heads above water and dollars in their pockets. It’s seemingly impossible to run a successful business in a society that has been built off of the oppression of marginalized groups and remain 100% ‘cruelty-free.’ Better never means better for everybody—and historically it never has.

In the past, girlbosses—or women who were working to better things through feminism, as they were called in their day—always had a tough relationship with inclusivity. During the 19th century, Susan B Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were the undisputed leaders of the suffrage movement. They organized the conventions, wrote the newspaper articles, and were ultimately successful in passing the 19th amendment in 1920. But they didn’t accomplish all of that without throwing non-white women and black men under the bus that carried them to the ballot box.

In 1870 the 15th Amendment was ratified. The amendment prohibits each state from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen’s “race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” and it was wildly controversial at the time. The suffragette community was divided between those who were enthused about the amendment and those that sneered down upon it—Anthony and Stanton were a part of the latter group. The pair pandered to southerners by arguing that if educated and upper-class white women like themselves earned suffrage, that they could drown out the votes of undeserving men of color.

Stanton herself went as far to say, “Think of Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Tung, who do not know the difference between a monarchy and a republic, who cannot read the Declaration of Independence or Webster’s spelling book, making laws for their female betters” in 1869. Anthony never openly spewed racist rhetoric of that nature, but she recognized that she would need to appeal to white supremacists in order to achieve her goal and continued to work alongside people like George Train whose slogan was notoriously ¨Woman first and Negro last.¨

Neither Susan B. Anthony nor Elizabeth Cady Stanton lived to see the day when women or men of color were actually allowed to vote without serious pushback, but their behavior during this time effectively tainted their legacies and labeled the overall reputation of mainstream feminism as being very white-centric.

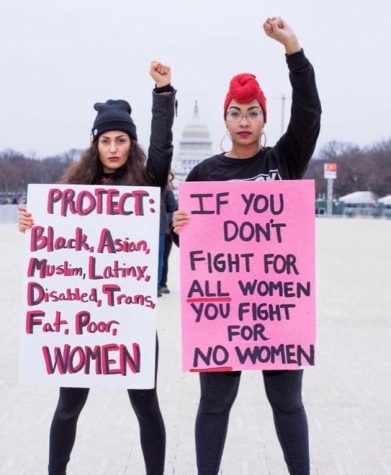

It would be comforting to be able to say that feminism’s reputation has bounced back in the 21st century, but evidence as recent as 2017 proves otherwise. The first Women’s March was held a day after President Donald Trump’s election and the event was widely celebrated and was dubbed the largest single-day protest in American history. However just two years later Women’s March Inc. faced allegations regarding their anti-semitism and use of the hundreds of thousands of donated dollars to focus on issues that pertained mainly to white women while ignoring those of women of color.

Sound familiar?

The girlboss dilemma isn’t new. It didn’t start in 2014 when the word became relentlessly plastered all over items, but rather decades prior. And it’s complex enough that it hasn’t really been explored until very recently. When we talk about a girlboss we’re talking about a woman who managed to be wildly successful despite whatever perceived patriarchal boundaries stood in her way; however, both distant and recent history has shown us that those types of women rarely exist without already having some kind of privilege that allows her to do so. This raises the question of whether or not we should be celebrating these women at all—which isn’t a simple one to answer.

On one hand, absolutely! By adopting a ‘don’t hate the player, hate the game’ type of logic, one could argue that girlbosses have already done so much good by smashing glass ceilings and setting examples of what ‘strong women’ look like for young girls, and that other factors are irrelevant because of that. But on the other hand, people are quite tired of the game that has been running in this country for years and know that it won’t be possible to dismantle it with the help of feminism that only uplifts one particular type of woman.

Angela Davis, renowned activist, once said, “Those who are already high enough to reach the glass ceiling are probably white and then if they aren’t white they are affluent because they’re at the top. All they have to do is push through and crack the glass. It has always been clear to me that any feminism that solely privileges those who already have privilege is bound to be irrelevant to poor women, working-class women, women of color, and LGBTQ women.”

No young woman wants to be seen as incapable, unintelligent, or unaccomplished, because that perception only allows untrue stereotypes about their gender to be perpetuated even further and it diminishes other people’s willingness to respect them. But people can get so caught up in doing the work and going the distance that they end up compromising their character and doing whatever they can to hoist themselves up—even if that means pushing somebody else down. This is a pattern that can be seen in some successful women, and more often than not it ends coming back to haunt them and stain what they’ve worked so hard to create.

A way to avoid falling into the girlboss trap is to recognize that there is more than one way to be a good leader, and that it is possible to become successful without utilizing harmful or hurtful practices. This is no easy feat. It’s much simpler to look at people that have achieved great things and turn a blind eye to their transgressions, rather than think critically about these role models and their behavior. But by practicing the latter, we open ourselves up to having honest conversations about the inequities that we still face.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with wanting to have a T-shirt that says “SCREW THE PATRIARCHY” in bright pink letters or a keychain that has the word “#bossbabe” engraved in it—some of that stuff is cute! But when a person’s advocacy is limited to them buying trendy things on Etsy and reposting aesthetically pleasing infographics on their Instagram stories periodically to make sure that their friends don’t think that they’re a bad person…there’s an issue. At the end of the day, it all boils down to action: to uplifting different types of women in both personal and professional spaces and collectively working towards a more equitable reality for us all.

Blair Martin is currently a senior at Homestead High School. She’s beyond psyched about continuing her work in the pubs lab and using the lessons she...